Jordan Wright

April 18, 2012

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network.

A good surfer must be in complete harmony with the vagaries of nature. Surfing is a unique sport in that its skilled athletes must alternately strive to conquer and surrender and must be emboldened and yet chastened by the force and changeability of both wind and water. Those requirements are non-negotiable. To succeed on a big wave a surfer must strike a perfect balance between physical strength and humility.

The business of modern surfing has evolved into a multi-billion dollar industry, Surfboards, wet suits, fashionable surfwear and more fuel an increasingly powerful market. Upping the ante, niche travel agencies now offer hardcore surfers vacations to exotic oceanside destinations around the globe. And though prices average $1,000 for a starter longboard, one New Zealander handcrafts paulownia wood boards that sell for over half a million dollars. But it has not always been a dollar-driven pastime.

Around 2000 B.C. indigenous populations began migrating out of Asia and into the Eastern Pacific. During that period ancient Polynesians journeyed to the area defined by New Zealand (Aotearoa) at the southernmost point, Tonga and Samoa along the western boundary, and the Marquesas to the east, eventually making their way to Hawai’i in the fourth century A. D.

Evidence contained in Captain James Cook’s log of his third trip to Hawai’i in 1778 record the existence of standup surfboard riding as practiced by Hawaiian kings at Kealakekua Bay on the Kona Coast of the Big Island where they rode standup olo boards. But for Papua New Guineans who had been riding the waves on their stomachs and referred to their belly boards as “splinters”, surfing took on a bold new dynamic in the 1980’s when an Australian pilot came there on holiday in search of the perfect wave. It was then that “Crazy Taz”, as he was known, left his surfboard behind and the cultural landscape was forever altered.

For Californian Adam Pesce who honed his passion for surfing on the legendary Rincon Beach in his hometown of Santa Barbara, a proposed trip to Papua New Guinea (PNG) was the dream of a lifetime. Inspired by an article in a surfing magazine, he took off with friends in 2004 to Papua New Guinea (PNG) part of a string of islands off the east of the Malay Archipelago in the South Pacific. He had taken a simple documentary film course and was eager to shoot the local surfing scene for a film he planned to make while hitting the waves along the island’s famous sea breaks.

After three months of research shooting he returned to California and seeing the video he had shot, he realized the travelogue-style footage did not have the makings of a film. He abandoned the project until 2008 when he got a call from Andrew Abel, President of the Surfing Association of Papua New Guinea. Abel told him they were planning their first national surfing championships in PNG and the trials would determine who would represent the country at the world surfing games in Australia. When Pesce heard this he realized the upcoming event could be the center of his movie and he returned to PNG in 2009 to begin shooting.

Armed with nothing but camera gear, a few surfboards and a degree in diplomacy from Occidental College in L.A., Pesce lived among the natives for seven months where he would become director, producer, editor and cinematographer on his first film, Splinters.

Of the 850 languages spoken throughout this Indonesian island chain of 5 million people, the most common is Melanesian Pidgin (Tok Pisin). Pesce began his stay by learning the language without a translator. He moved into an old shack with one of the local surfers who planned to compete in the surfing championship, and started shooting between bouts of malaria. His goal wasn’t to make a “surf movie” –- he wanted to tell the story of how one surfboard changed a culture.

The seaside community of Vanimo in Papua New Guinea where Pesce set up production is not as idyllic as it appears at first glance. The small village and surrounding country are a shape-shifting and complex culture clinging desperately to a primitive past. Up until recently, cannibalism and “cargo cults” were still practiced in the more remote outposts and today its citizens maintain a strict patriarchal society even as it becomes increasingly westernized through mining and fishing.

Caught between ancient taboos and emerging cultural changes, the country’s struggles are often more sociological than economic. For example brides are still bought by men through a “bribe price” or dowry, in which payment to the bride’s family allows the husband to physically abuse his wife. Domestic abuse is part of the film’s portrayal of family life on PNG, which includes strong scenes of men abusing their wives and even children in full view of the other villagers.

Splinters is the first feature-length documentary about the evolution of indigenous surfing in the South Pacific and the near fanatical obsession of the island’s surfers. But it is also a highly compelling story filmed in cinema verité style and told by the subjects themselves. It is their personal struggles and triumphs set against the backdrop of a lush tropical paradise that is at the heart of the film.

The film focuses on surfers from two competing surf clubs – the Sunset Surf Club and Vanimo Surf Club. Angelus, the son of the first native surfer in Vanimo, and Ezekiel, his protégé, are surfing rivals in the remote seaside community of Vanimo Village, where nearly everyone is related by birth or marriage. They dream of achieving prestige in their village by competing in the local surfing championships and ultimately competing against world-renowned surfers in Australia. For both the men and women, it’s their only ticket off the island and a chance to see the world.

The film also follows two of the island’s most accomplished female surfers, Lesley and Susan, who are sisters. Both need to gain acceptance into one of the all-male surf clubs in order to enter the competition. Lesley is the bolder of the two women. Alternately capitulating to the men or standing her ground, she cannily walks a social tightrope, using maneuvering techniques as deft as those she excels in when riding a wave. Susan on the other hand is more conventional and accepts the subservient role women are taught to assume. Yet each becomes instrumental in altering the current culture’s groupthink.

In a pivotal scene Abel tells the men that in order to compete nationally the women must be accepted into the clubs. Despite centuries of culturally sanctioned male dominance, the men must learn to sublimate their egos and accept the women as equal participants. For the men an even greater challenge than compromising ancient societal rules, is the simple act of getting along with one another as old clan rivalries flare up and threaten their chances of entering the contest. It is only when the teams begin to work together and the women are included that they begin to see what they can achieve.

Interspersed with the surfing and breathtaking scenery are flashes of violence. In one incident a woman is severely beaten by her husband to the encouragement of his neighbors, in another the men threaten each other in a drunken nighttime road rage incident. The scenes are brutal and graphic, but Pesce felt it vital to portray the reality of life in PNG.

Splinters brings to the screen an intimate and emotional portrait of a culture tragically trapped in a violent past. By showing how surfing can serve as a catalyst for social change and gender equality, the film attempts to prove the axiom that society can only advance when each and every citizen is inherently invested in its future success.

Last month ICTMN spoke with Adam Pesce by phone from his home in Santa Barbara, California.

ICTMN: How long ago had the people of Papua New Guinea been surfing?

Adam Pesce: The elders told me that as long as they can remember they were belly surfing on broken pieces of their dugout canoes. When that surfboard was left behind in PNG on the 1980’s, they first transitioned from belly-boarding to standing up.

What attracted you to make a film on surfing involving indigenous people?

It was a mix of several interests. I grew up surfing in California where I was studying international relations and had an interest in travel. I decided to go explore in Vanimo. I was definitely interested in the Western values associated with the surfboard and how they would mesh with local traditions.

When you began shooting in PNG were you surprised by the harsh traditions still practiced there?

I didn’t know how ingrained these traditions were going to be and once I was on the ground there were these walls they put up. I saw women butting up against them and these women were definitely the trailblazers.

Were you ever afraid?

I definitely was afraid for myself. The threat of violence was always there. Things can always turn on a dime.

Have you gone back to show the film yet?

I’m looking forward to bringing the film to Vanimo and showing it to the people and planning an event around it. There’s talk of bringing it to the championship [World Qualifying Series] surfing event in Vanimo in 2013. However Andy and Ezekiel [one of the surfers in the film] were able to come to New York and to see it at the Tribeca Film Festival this spring.

How did it affect them?

It was an overwhelming experience for Ezekiel who ended up in New York doing a press event at the screening of a film he had starred in but never seen. I was very concerned that he might not like the film or how he was being portrayed or that it would be inaccurate in his mind. In PNG men will hold hands as they talk or walk around the village, so we held hands throughout the screening and after the credits he turned to me and said, “Thank you”. It was a very special moment for me — knowing that he enjoyed the film.

Did you ever speak with him about male to female relationships on PNG and how their society might evolve as a result of the surfing competition?

I didn’t have that conversation with Ezekiel, but I did speak to Andy at length following the screening of the film and he was really taken aback with the seriousness of the way surfing could really elevate the status of women in PNG. And I know he is doing his best to make sure that women have access to surfboards and have opportunities to compete and travel.

I would like to add that I’m looking to collaborate with a domestic violence shelter in Vanimo, where people will be able to contribute to a place for women seeking legal aid and physical refuge, and that the film will be screening at the Human Rights Arts and Film Festival this spring in Melbourne, Australia.

Splinters has been a huge hit on the indie film circuit and has been the Official Selection in film festivals from London to Warsaw to Newport Beach and was voted “best Documentary” by Surfer Magazine. It is available for rent or purchase on iTunes or go to www.splinters.com for 2012 screenings in your area.

Jordan Wright

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

April 15, 2012

A mess of ramps ready for the pan - photo credit Jordan Wright In Qualla Boundary, high up in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, springtime means foraging for emergent greens. The Eastern Band of Cherokee has always used the tender shoots, chockfull of minerals and Vitamins A and C, as both tonic and food source – an antidote for winter’s ailments as well as sustenance.

Some of the earliest wild edibles are sochan (a relative of the green-headed coneflower), watercress, branch lettuce, creasy greens and ramps – the most treasured of all. Big Cove tribal council member Bo Taylor gives the Cherokee word “anitse” for all spring greens and “wast” to refer to ramps.

A small adaptable plant that grows only at elevations of 3,000 feet or higher, the noble ramp (Allium Tricoccum – Liliacae) is venerated by the southeastern Cherokee who passed down its virtues to the early settlers. “According to our tradition we use ramps to cleanse the blood from toxins built up over the winter months,” Cherokee tribal elder Don Rose explained.

Throughout local communities there is a movement afoot to preserve, protect and propagate the plant that has a brief season in the deciduous woods before the tree canopy reappears. Horticulturalist and ethnobotanist Kevin Welch, who heads up the Center for Cherokee Plants, has created a project in Qualla called “The Backyard Ramp Patch”. “Each spring we distribute small bags of ramps filled with around 50 bulbs for home gardening.”

His wife and collaborator, Sarah McClellan, who is the Project Director and Educator at the Cherokee Reservation Cooperative Extension Center and coordinator of the Cherokee Native Plant Study Group is enthusiastic about the program. “We have distributed over 70,000 bulbs so far. It’s our ninth year and we are supplying to 150-200 families each year.” They are not taken from the forest. McClellan buys the ramp bulbs and seeds from Ramp Farm Specialties in Richwood, West Virginia.

Harvesting Ramps - Photo credit Jordan Wright Welch talks about the proper way Indians harvest them in the wild. “The best method allows ramps to grow back from its roots. Rather than pull up the entire plant, they loosen the soil around it, then reach down into the soil with a knife and cut off a ¼ inch or so of the bulb just above the roots, leaving the roots in the soil to grow a new plant. Thus ramps continue to flourish. When pulled up by the roots, like onions from the garden, whole stands of ramps disappear,” he cautions.

Each year the community hosts “Rainbows and Ramps” in April. Janice Wildcatt, who runs the early spring event and acted as my guide during a recent trip to Cherokee, NC, explains, “The festival has been going on for 30 years. It’s a celebration for the tribal elders, who can no longer get into the woods to pick their ramps. Before the visitors arrive we give them a free meal of ramps and local trout and other traditional foods. It’s comfort food. Way back it was more like a simple pot luck, but it has grown in popularity and for the past two years we have served over 700 visitors a year.” Entertainment is part of the experience and this year’s festivities included the Head Start Traditional Dancers along with the Old Antioch Gospel Singers and the Mountain Traditional Cloggers.

Blackberry dumplings - photo credit Jordan Wright During my stay I was invited by several tribal members to join them in a dinner showcasing traditional Cherokee foods. The women who are generous in the community with their time and culinary talents laid out a splendid buffet of their delicious dishes. Nikki Nations, a local landscape artist, cooked up fatback, blackberry dumplings, fried potatoes and lye dumplings; Alice Kekahbah, who lived and worked for the BIA for 30 years, prepared her fried sweet potatoes and sochan; Bessie Wallace, President of the North American Indian Women’s Association (NAIWA) Cherokee Chapter, brought sweet tea; Hattie Panther made bean dumplings; and my tourism guru, Janice Wildcatt, sautéed up a mess of ramps with scrambled eggs. It was a convivial evening among the ladies who caught up on local happenings. After supper we drove over to Big Cove where we spotted two of the recently reintroduced elk herd peacefully grazing alongside the road.

Elk in Big Cove, Cherokee, NC - photo credit Jordan Wright Ramps are frequently described as having an acquired taste akin to onions mixed with garlic, and are often referred to as “wild leeks”. At some ramp fests they even hand out mouthwash, called the “Scope cure”, to counter what they say is the lingering odor.

Returning from Cherokee we spent a few days at our family homestead along the Blue Ridge Parkway in the Appalachian mountains of southwestern Virginia. Beside a small spring I located a stand of ramps that had been planted over 30 years ago. Bearing in mind the Cherokee way of sustainability, I harvested a small bunch, carefully leaving the bulbs intact underground for next year’s crop. After rinsing the dirt off the leaves and drying them, a quick chop and sauté in butter revealed them to be even milder than scallions and with a delicate aroma of garlic. The only thing missing was the trout.

Jordan Wright

March 2012

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

Terri Rofkar's Lituay Bay Robe Teri Rofkar (Tlingit of the Raven Clan from the Snail House) of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska sees patterns and shapes emerge from wool and roots. Using cedar, spruce tree roots, ferns, and mountain goat wool she collects in the woods, and along the shoreline of her Northwest coast home, the internationally renowned artist has been weaving exquisite baskets and textiles for over 25 years. Her robes are made with traditional Sitka freehand weaving techniques that date back over 6,000 years. Descending from a family of weavers she is inspired by “a deep connection to my ancestors.”

In creating ceremonial regalia she weaves in the once lost art of the Tlingit Raven’s Tail style of twining that uses ‘formline’ figures to represent the creature or spirit. Rofkar’s expertise also extends to the more highly stylized and representational Chilkat style of curvilinear and circular forms, one of the most complex weaving techniques in the world and the only one that can create perfect circles. Chilkat robes feature long wool fringe and are used for both ceremonial as well as dancing robes.

But though these loom-free techniques derive from an ancient culture, Rofkar is not wedded entirely to the past. “I listen to heavy metal when I work,” she cheerfully explains debunking the notion that she is a strict traditionalist unwilling to experiment with new concepts as an artist. “Change is the one thing that is constant. Traditional arts continue because they adapt and change with society. I’m not changing the methodology. It is the same as it was thousands of years ago. My technique and my intent are still there.”

Her latest project the “Tlingat Superman Series” will comprise three ceremonial robes, two of which will use modern technology. She credits a seminal meeting with the noted anthropologist and textile expert, Alice Kehoe, who spoke to her of “extending yourself beyond what you might be capable of” that drove her to explore new ways of applying her technique.

Teri on the beach with mountain goat wool The first and most traditional robe, which Rofkar estimates will take over 2,300 hours, will be in the earlier Raven’s Tail technique and will be woven from mountain goat wool that she spins herself. “These robes are created all by hand. It’s the same kind of textile you see with Kennewick man, found 9,000 years ago in Oregon, or the mummies of South America, discovered around 30,000 years ago,” she elaborates. “The patterning on the robe will be accurate. Design work and art was our written language. Our village goes back 11,000 years with its stories of flood times and when the ice advanced.”

The complexity of the Tlingit style of finger weaving is well known. “We used math and science, but we didn’t use Western terminology for it. So in the Western mind it didn’t exist. Weaving is all math and not many numbers,” she says.

Drawing from symbols of animals and clan crests spoken of in Native oral history, traditional robes can often include headpieces with frontlets that might include sea lion whiskers or shells. “In Alaska our top predators have been bears and killer whales and I plan to weave grizzly bear tracks and killer whale teeth patterns into the robe.”

As an eco-conscious artist and 2004 Buffett finalist for Indigenous Leadership, Rofkar is concerned with sustainability and stewardship of natural resources and her passion is palpable. Some of the trees she sources from are hundreds of years old and known to her family for generations. “Tlingit culture recognizes that animals, plants, people and places all have spirits and American Indian relationships to the earth are great examples of this. Native people left the land sustainable and preserving the environment is a part of the Indian community since we’re so in tune with it,” she asserts. “In fact when the invaders came it was like, ‘Hey! There’s nobody here!’ ”

Following this philosophy she will use locally found copper and hemlock bark for the coloring and mountain goat for the wool. “I just found an ancient population of mountain goat for my wool fiber source,” she reports. In addition she will use her beadwork skills to describe the building blocks of life, “I will incorporate the double helix [into the robe], because it represents the proteins of amino acids. “

In 2010 Rofkar visited the Kunstkamara Museum in St. Petersburg where she viewed the largest collection of the oldest Raven’s Tail robes. “They had six robes. All acquired in Lituya Bay in 1788. They realize how important they are. I had no idea they came from that area. Ten years earlier I had woven my Lituya robe that was all about my clan group and the fault lines and plate techtonics and megatsunamis of the area. It sure gave me the context of why I’m so obsessed with them.”

Another robe will be created from Kevlar, a bulletproof fabric. It’s what she defines as her “tongue-in-cheek” reference to the Sitka park rangers who wear bulletproof vests. “In our Native communities there isn’t even any car theft. We only have 14 miles of road here. When we’re in our cars we call it joy riding!”

Of the recent use of Native images for ‘homeland security’, she explains, “There have been a plethora of images for the term, so this is my political statement. They [the park rangers] are the people that are the caretakers of our sacred ground. It’s not for protection from the bears that they wear it.”

“When I do my patterning on the Kevlar robe I will use those top predator patterns and do it accurately. It will be where science and art meet to tell the stories of legends and dance – to stretch our creativity. When I first came up with the concept I didn’t tell anyone for a while. I knew it was risky,” she admits. “But I knew if I didn’t get it out there it would haunt my dreams.”

The final piece in the series is called, “The Robe of Enlightenment”. It is inspired by the Maoris of New Zealand whose ancestral war chants sung during their rhythmic Haka dance is also used by Hawaiian football teams before a game or after a win. Rofkar recognized elements of Maori symbols that are similar to Native Alaskan weaving.

Haka is the theme song for this robe. It has the embodiment of the “Okay, we’re ready. Bring it!” she emphasizes. She also acknowledges being inspired by Del Beazley’s popular Hawaiian Maui “Superman” song. “I think it embodies leadership. And I’m looking for a hero. Before there was a Clark Kent there was a Superman.”

Rofkar weaving a continuum robe In this garment her strategy is to fuse luminescence and nanotechnology into the fabric. “I visualize it as the warps are fiber optic and could be in an audio frequency that gets louder, and the wefts are embedded with nanofibers that are aluminum and programmable. Tassels and lights could be embedded too and change color, “ she describes, “much like the story of the raven changing color.

As a lecturer and educator Rofkar has taken her woven arts to the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In 2006 she was the Native Arts “Smithsonian Visiting Scholar” at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) and in 2004 she won the Governor’s Award for Alaska Native Arts.

She received a USA Fellowship in 2006 and performed at the inaugural USA Fellows Celebration at Jazz at Lincoln Center dressed in one of her spectacular robes. In 2009 she was awarded the National Cultural Heritage from the National Endowment for the Arts, the highest honor in the folk and traditional arts.

She is aware of her responsibility to the craft. “I am really challenged to incorporate today’s fabrics and technology into the traditional textiles because those are the textiles of this generation. I thought how awesome it would be to take the regalia to the next level where it would be programmable, where I could integrate the knowledge that young people have today with music and sound and hip-hop into the Robe of Enlightenment.”

Reflecting on the future of art and its relationship to technology she muses, “If we don’t use our creativity and stretch it in ways that it hasn’t gone before, how do we know what the applications are. When we go into space we learn a whole lot about what our technology is and can apply it to other things. I think that this kind of thinking is something that has been missing.”

Acknowledged to be one of the few living practitioners of the Tlingit woven arts, she ventures, “I thought, I’m the one carrying the culture forward by doing the weaving and creating the pieces, and all of them have extensive stories about plate tectonics and earthquakes, mega tsunamis and migration. I feel I am just the conduit. It’s the twining that is moving through me.”

Rofkar’s work can be seen at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and the Museum of the North in Fairbanks, Alaska.

Special to Indian Country Today Magazine

Jordan Wright

March 2012

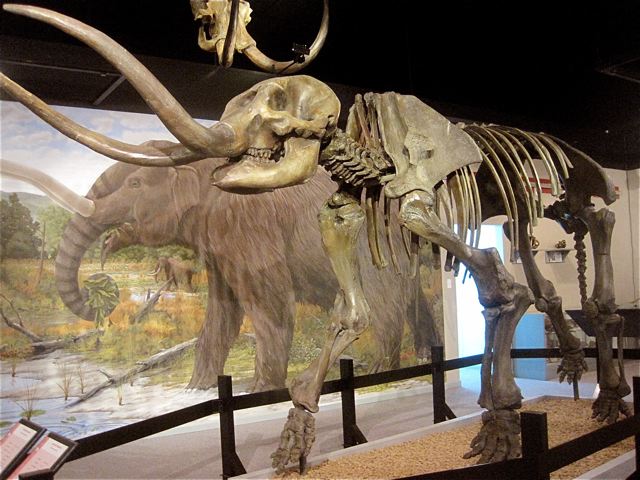

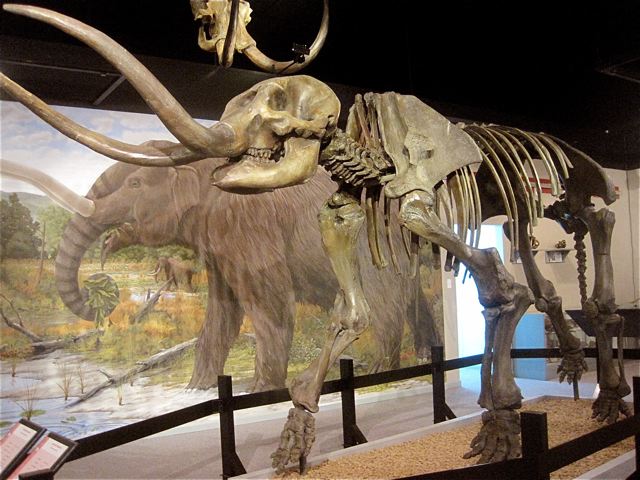

Mastodon skeleton at the Museum of the Middle Appalachians - photo by Jordan Wright “Saltville can probably claim to be the most fascinating two square miles in Virginia, or possibly the eastern United States, owing to its geology, paleontology, history and past industrial production.” Charles Bartlett, American geologist.

Around Halloween last year when the 2,077 residents of Saltville, VA heard the producers of Animal Planet’s“Finding Bigfoot” were coming to investigate a sasquatch in their midst, phones rang off the hook. The program’s host Matt Moneymaker called for a town hall meeting at the Palmer Grist Mill and anyone who had seen Bigfoot up in the Southern Highlands was asked to bear witness. Moneymaker couldn’t attend in person. He was already up near Gum Hill that night with his infrared cameras in search of the “beast”.

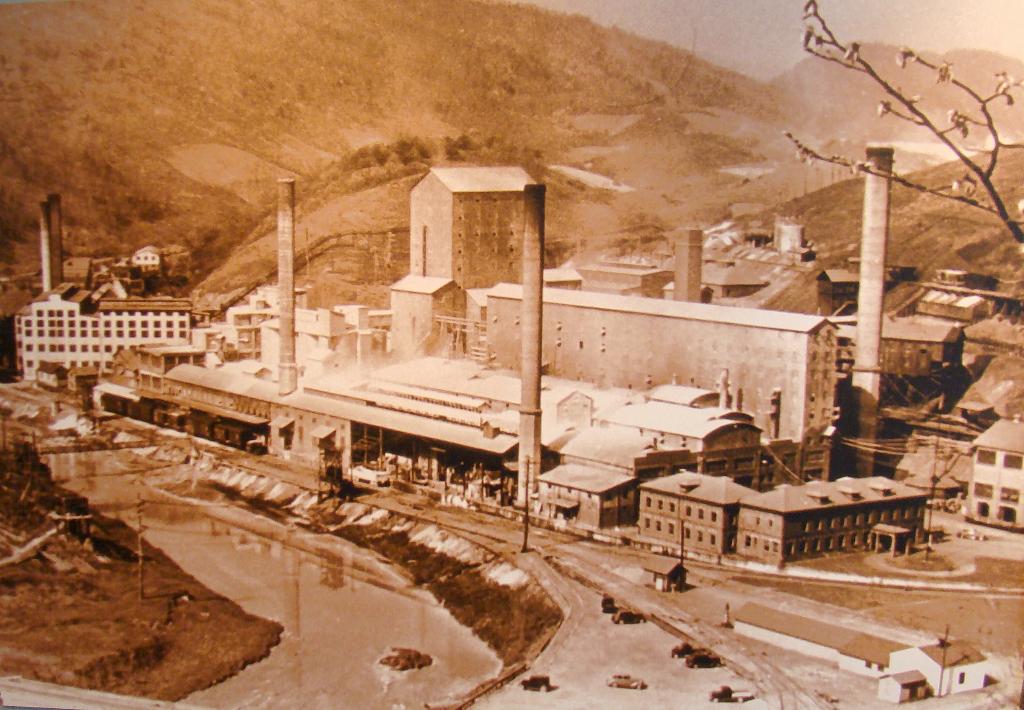

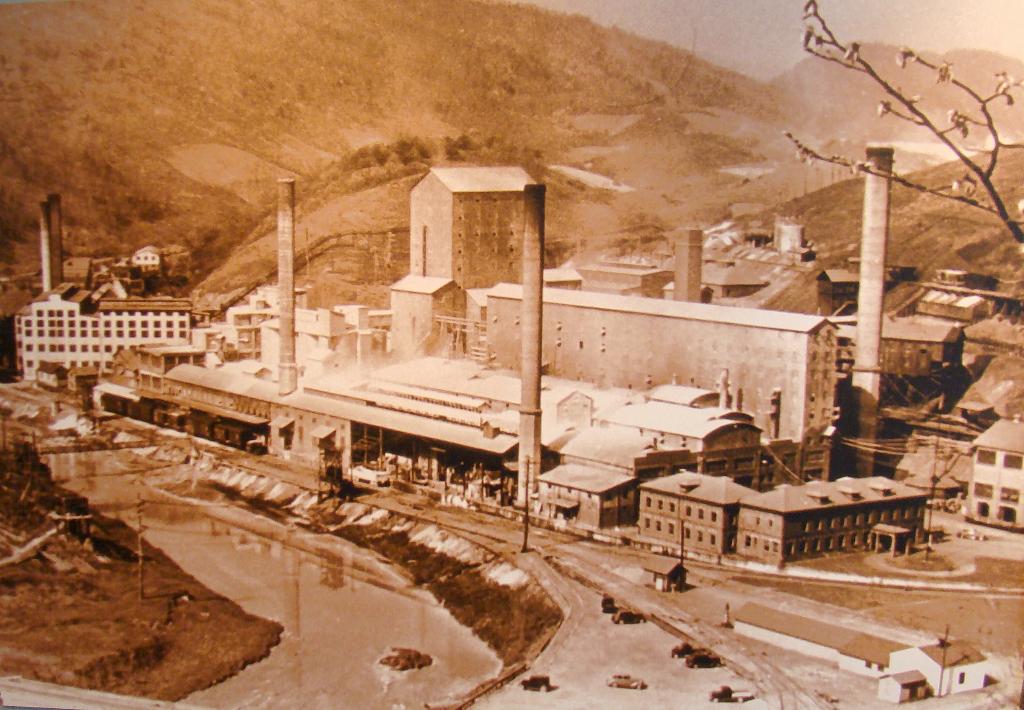

MOMA - Olin Salt Factory But the small town in a quiet valley has known a great deal more excitement than the random sighting of a mythical creature. In a place where the bizarre presence of mallards and Canada geese paddling lazily in salt ponds in the middle of the Blue Ridge Mountains is commonplace, the unexpected is, well,ordinary.

Saltville’s inhabitants have always lived at the crossroads of history because of salt. The quest for the coveted mineral lured prehistoric animals and hunters. Tribes from the region used it for trade and later industrialists made fortunes selling it to the nation. Salt’s powerful influence held sway during the Civil War when Union forces fought a 36-hour battle to capture Saltville and destroy its crucial saltworks. It is not a simple story to tell. It’s a story of war and survival, but also of power and prosperity.

MOMA Indian Artifacts Despite what is found in most American schoolbooks, our early history did not begin with the emergence of the dinosaur and miraculously pop back up with the British landing at Plymouth Rock. Aboriginal people migrated down the continent from Alaska and up from Florida, the Caribbean and Mexico to arrive in this wilderness. In the area of Saltville Paleo-Indians dwelt along the Clinch and Holston rivers in Southwestern Virginia and on across the mountains and valleys into the adjoining territories of what is now known as North Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee.

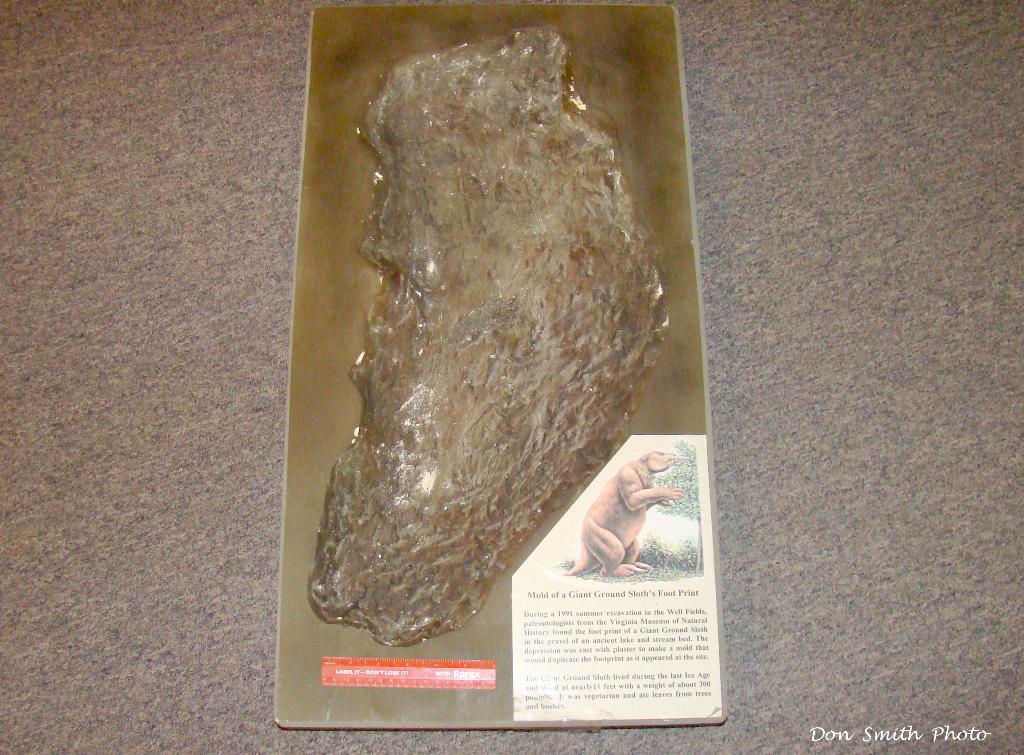

In the Pleistocene Age Saltville was a convergent point for prehistoric creatures like the great woolly mammoth, elephant-size ground sloths and hulking mastodons, who came in search of water and salt deposits for their survival. Over millennia these migrating herds carved permanent trails in the earth. Of six major Indian trails in Virginia three are found leading to Saltville, tracing the well-established paths of the animals that came before them.

MOMA Exhibit Indigenous Indian Author, archaeologist and professor emeritus at UCal Santa Barbara, Brian Fagan, lists the Saltville area as one of the six worldwide sites of earliest human activity and a known concentration of pre-Clovis spear points made by Ice Age hunters. The discovery of a tool-like bone fragment in the area, made by humans and found beside a mastodon, is evidence of its slaughter by prehistoric man.

For today’s visitor to Saltville, eight miles off I-81 in Smyth County Virginia, a compelling resource helps connect the dots. Chronicling the area’s complex history in a comprehensive timeline, The Museum of the Middle Appalachians is a mecca for archaeologists, paleontologists, historians and the curious.

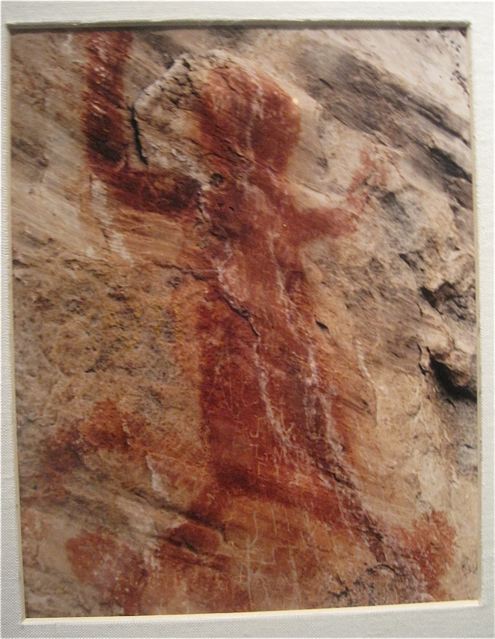

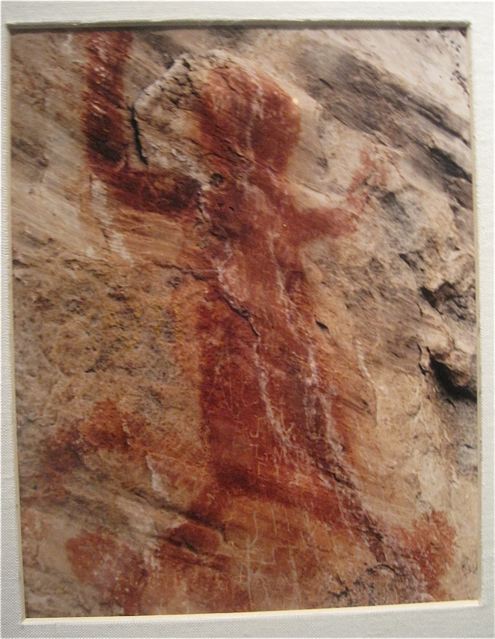

Paint Lick Mountain pictograph taken in nearby Tazewell County - Photo reproduction by John C. Fisher (Museum of the Middle Appalachians) The museum houses thousands of artifacts and archival photographs from the area dating from 14,500 years ago to the present and visitors are greeted with a breathtaking full-size replica of a mastodon skeleton and the jaw of a woolly mammoth. Mineral displays from geologic formations of the Late Ice Age show the earliest evidence of human activity in Eastern America.

The museum begins its American Indian displays in the Late Woodland Period (900 – 1600 BC) when the Chisca, also known as Yuchi, lived beside the nearby Holston River, which they called ‘Hogoheegee’ and their village ‘Maniatique’ where they established salt-powered chiefdoms and traded the precious commodity with tribes along the eastern US. Museum manager, Harry Haynes, says, “There have been more than 20 native village sites found along the Clinch and Holton Rivers within 20 miles of Saltville.”

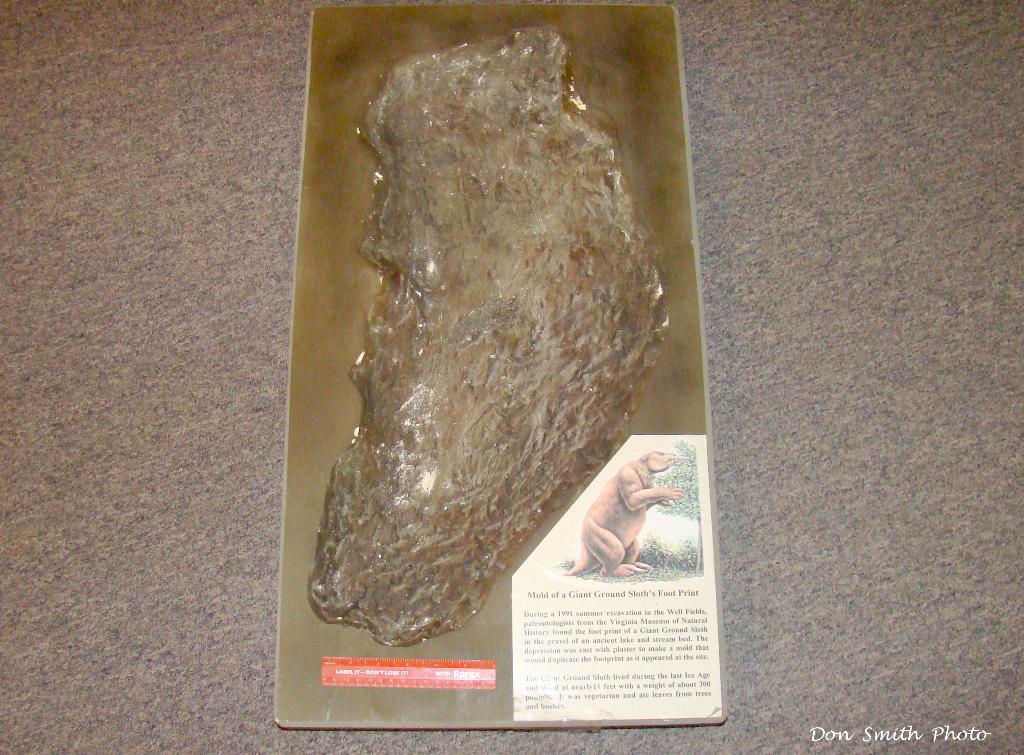

Mask gorget in the Weeping Eye style from the Museum of the Middle Appalachians- photo by Jordan Wright Clay pots, celts, copper and shell beads, including an astonishing 164-inch necklace of marginella beads make up a small part of the extensive Patricia Bass Collection. Mastodon bones, a beautiful quartz crystal grooved axe, and javelin points are other intriguing objects that have been unearthed in the area. Here a giant slothfootprint shares space with rare engraved gorgets, a type of medallion or mask with rattlesnake or turkey designs that were carved from marine shells.

Photographs of cliff walls at nearby Paint Lick Mountain show early pictographs of bird, man and snail. Further testament to Native American skill and craftsmanship, are drawers filled with axes, celtsand arrowheads and a rare platform pipe of steatite, highly characteristic of the region.

MOMA - Indigenous Indian Bead Craft Since 1782 when Arthur Campbell sent a letter to Thomas Jefferson and enclosed a jaw tooth from a mastodon, referring to “bones of an uncommon size”, researchers have been attracted to the region. In 1917 the Carnegie Institute conducted the first official excavations at Saltville, followed by the Smithsonian Institute whose findings beginning in the 1970’s led to the discovery of well-preserved mastodon skeletons and wooly mammothremains in 2007.

Exhibits reflect its later development as a “company town” under the aegis of the Olin Corporation who purchased the Mathieson Alkali Works that had extracted salt there since 1895.

MOMA - Civil War Solders Olin, who continued to harvest salt in the well fields later branched out into chemical production and developed the rocket fuel that took man to the moon. Even today over 23 tons of salt per hour is still produced here and former salt caverns serve as one of the nation’s largest storage facilities for natural gas. The town’s slogan “Preserving history for over 30,000 years from the Ice Age to the Space Age” neatly sums up its dramatic history.

In the 16th century Spanish conquistadors came searching for a mythical chimera other than the ‘sasquatch’. Archives reveal that in 1541 two outriders first set foot in Saltville in search of precious metals and a legendary kingdom of great wealth called ‘Chicora’. Diaries detail encounters with friendly Indians, but reports state that no gold or silver was found. This well documented meeting with the Chiscas was long before Captain John Smith set foot in Jamestown in 1607, and decades before Pocahontas was born.

MOMA - Paleo Casting Chemist and professor emeritus from Virginia Tech, Jim Glanville, explains, “The presence of Native Americans in Saltville is the earliest recorded in Virginia’s history. It is well chronicled in Spain’s archives through letters, testimony and diaries. A 1584 petition to King Carlos V of Spain by a Spanish soldier named Domingo De Leon tells of the bloody incursion and destruction of the village of Maniatique by a Spanish sergeant named Hernando Moyano in April of 1567 under orders from the explorer Juan Pardo and,” he emphasizes, cheerfully upsetting colonial historians’ apple cart, “that was forty years before the British landed at Jamestown.” By the time English-speaking settlers reached Saltville 175 years later all the local tribes were gone.

Glanville’s research, prompted by a Google search, pieces together evidence that, “the first Native American woman to be named in Virginia was not Pocahontas [as is commonly accepted] but Luisa Menendez, a resident of Saltville, who as a teenager married a Spaniard and later testified to the Spanish governor in St. Augustine, Florida her knowledge of the destruction of Maniatique.”

Saltville has many remarkable stories to tell along with mysteries and ancient artifacts yet to be revealed. During my stay I stopped along the town’s salt ponds to get directions from a boy and his friend out for a leisurely day of fishing. We spoke for a while of the many artifacts housed in the museum. He assured me that many more are still found close to town. He knew for a fact, he said, because whenever he needs pocket change he goes out and digs them up. Just remember if you decide to go fossil hunting on Gum Hill, keep your eyes wide open. You may catch a glimpse of the elusive bigfoot staking his claim as Saltville’s next chapter in history.

Where to stay

The historic General Francis Marion Hotel is a beautifully restored 80-year old grand hotel in nearby Marion. Complimentary continental breakfast. Lunch and dinner served in the hotel’s Black Rooster restaurant. www.gfm.com

Where to Eat

The Town House in Chilhowie serves upscale, locally sourced American Modern cuisine just off I-81 on the way to Saltville. Open for dinner only. Reservations highly recommended. www.townhouseva.com

In Marion the charming Handsome Molly’s Bistro and Small Wine Shop across from the hotel serves soups, salads, paninis and pizza.

In the area

The Museum of the Middle Appalachians, Saltville. Noted paleontologist Dr. Blaine Schubert of Eastern Tennessee State University conducts archaeological digs open to the public in summer. Visit www.museum-mid-app.org for dig opportunities and museum hours.

Saltville is on Virginia’s Crooked Road music trail and Friday nights are for old time bluegrass and gospel music. From 7 – 10 pm at the Allison Gap Ruritan & Community Center.

The Lincoln Theatre in Marion is one of only three Art Deco Mayan Revival theatres in the country. The $1.8 million dollar renovation has placed it on The National Register of Historic Places. For a schedule of events visit www.thelincoln.org

ICTMN magazine article – Click Here http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2012/02/12/the-most-fascinating-two-square-miles-in-the-eastern-united-states-95733

Jordan Wright

November 26, 2011

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

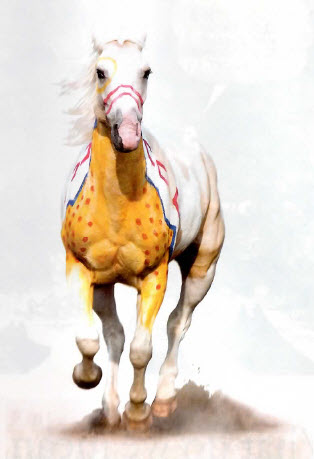

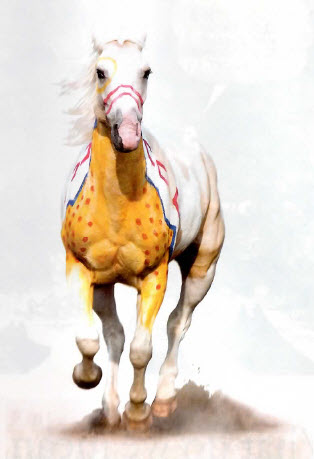

Crow War Pony painting by Kennard Real Bird, Crow

Out of the earth

I sing for them,

A Horse nation

I sing for them,

out of the earth

I sing for them,

the animals

I sing for them.

Sung by Lone Man of the Teton Lakota – From the book “A Song for the Horse Nation”, edited by Emil Her Many Horses (Oglaa Lakota) and George P. Horse Capture (A’aninin).

As much poem and prayer as personal tribute, this song shows the respect and reverence American Indians have accorded the horse. For the past three centuries this noble beast has been indispensable to their existence during times of war and peace, altering the landscape of daily life for its caretakers.

The bond between the horse and Native peoples is the focus of the National Museum of the American Indian’s recently opened exhibition, “A Song for the Horse Nation” in Washington, DC. Originally shown on a smaller scale in New York City in 2009, the show has grown to include a sixteen-foot tall Lakota tipi adorned with horse and warrior hand-painted pictographs and fifty additional objects, along with life-size horse and dog statues displaying a Tsisistas/So’taeo’o (Cheyenne) travois ca. 1880, a type of sled made of wood, pigment and hide, commonly used for transporting goods and people.

Rifles belonging to Geronimo (Chiricahua Apache), Chief Joseph (Nez Perce) and Chief Rain-in-the-Face (Hunkpapa Lakota) are also highlights of this spectacular exhibition.

Winter Count on cloth by Long Soldier (Hunkpapa Lakota), ca. 1902. Fort Yates, North Dakota. Muslin cloth. With the advent of the domesticated horse came an unparalleled defense for the Plains warriors, who could ride great distances as well as provide an expeditious escape from the firepower of advancing troops. It served as a vehicle for transport of possessions and people and allowed tribes to roam more freely during hunting season affording them more leisure time to pursue art, spirituality and philosophy. Primitive pictographs of horses painted on muslin reflect daily life, showing the versatility of the horse for hunting and battle as well as horse raids and courtship.

Horses were bred not only for daily use – the hunting of bison was made considerably easier while mounted on horseback – but also for trade, proving to be an excellent commodity in exchange for food, eagle feathers and tobacco. We learn from the exhibit that in the 1800’s a single horse could be traded for 10 guns, 5 tipi poles or several pack animals.

Though the exhibition features objects predominantly from the 18th and 19th Centuries, two of the oldest objects on display are a Spanish Conquistador helmet from the late 1500’s-early 1600’s, on loan from the Autry National Center, and a Seneca comb from around 1600 made of antler with a carved figure of a horse from the George Gustav Heye collection.

Drawing from the museum’s extensive collection of horse trappings as well as artifacts, artwork and personal accounts, are a Menominee wood saddle carved in the shape of a horse ca. 1875; a Northern Cheyenne quilled horse mask; No Two Horns (Hankapapa Lakota) dance stick; a Lakota hide coat embroidered with horse motifs; and historic photographs from the museum’s archives. Along with elaborately beaded regalia and tribal objects, are also stunning works from contemporary artists.

Glass horse mask, 2008, by Marcus Amerman (Choctaw, b. 1959), New Mexico. Multicolored glass. Glass horse mask, 2008, by Marcus Amerman (Choctaw, b. 1959), New Mexico. Multicolored glass.

Marcus Amerman’s (Choctaw) multicolored glass horse mask is a particularly dramatic piece that echoes the celebratory beaded masks still used in rodeos and mounted parades. The sculpture shares space with “Crow War Pony”, a spectacular photograph by Brady Willette of a war pony, painted in tribal symbols, by artist, rodeo bronco buster and horse whisperer, Kennard Real Bird (Crow) whose family’s ranch lies alongside The Little Big Horn River in Montana, and who is known for his annual reenactment of the Battle of Little Big Horn that draws visitors from around the world. The painted pony is named “Cool Whip”. Trained by Real Bird, the palomino was eventually sold to a family in Minnesota where he has garnered his own notoriety.

It is fitting that Emil Her Many Horses is the curator of this equine exhibit. A member of the Oglala Lakota nation of South Dakota, Her Many Horses is a specialist in Central Plains cultures. His paternal great-grandmother was called Many Horses Woman, meaning she owned many horses, a symbol of wealth and generosity.

“All horses used by Native Americans throughout North America and Canada originally descended from 25 Andalusian horses brought over by Christopher Columbus on his second voyage in 1493 to Hispaniola [now the Dominican Republic] in the West Indies, eventually making their way through Mexico and Florida and into North America where Plains peoples adopted the horse,” he explains.

“A display map shows California horses going up North, and then the French and Dutch to the East Coast later. With the Pueblo Revolt horses came into Native hands, and then it would be the Navaho, the Arapaho, the Pueblos and the Commanche who have horses. Then they are traded up North, but the Commanche are known to also trade them up to the Shoshone.

I think what we tried to show was really the impact of horses and hunting, because with horses you were able to secure more game such as buffalo and if you could secure more game you had more resources. Since if you didn’t have horses you were hunting buffalo on foot. So the thing that happens is that tipis become bigger because you have more time to make a tipi.

In warfare, other communities who may have been an ally in the past, if they had this resource and you wanted it, it would cause conflict with people that were once allies. But horses also helped in preventing the onslaught of the cavalry and settlers. It kept them at bay.

Possibly Chief Eagle of the Salish (at right), with an unidentified woman on horseback, ca. 1905, St. Ignatius, Montana, on the Flathead Reservation. Horses also would have an impact on how you traveled. It was either the woman or the dog that would have to carry the material while the men were guarding as they moved camp, because at any time they could be attacked by an enemy scouting party. So it was either the dog or the woman that would carry the material. But when the horses came it made for a swifter getaway. You could be out of there much quicker than to try to wrangle a dog.”

When asked what he hoped visitors would take away from this exhibition, he offers, “It really is the close association with horses that we still have today. For some the horse is very vibrant, still a part of their communities. For some of us it will always be a part of us through our stories, our culture, and our artwork even though we no longer own any horses. But they’re still rich in our culture, our memory and our knowledge.

“A Song for the Horse Nation” runs through January 7, 2013 at the National Museum for the American Indian in Washington, DC. For more information visit www.AmericanIndian.si.edu/exhibitions/horsenation.

Jordan Wright

October 27, 2011

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

Opening ceremonies at Patuxent River Park's American Indian Festival - photo credit Jordan Wright On an autumn afternoon with the sun at its apex in a clear blue sky, we traveled down a country lane to Maryland’s Patuxent River Park. Silhouetted against the deep green of the pines and American holly, the trees had begun their brilliant burst of color, the crimson of the dogwood, the lemon yellow of the tulip poplar and the pumpkin orange hue of the sugar maple. A tantalizing aroma of venison stew and fry bread hung in the cool crisp air, and cars had begun forming long rows in the freshly mown fields.

Park Service Naturalist Beth Wisotzsky with baby owl - photo credit Jordan Wright Set on 7,000 acres of protected woodland and watershed, the park meanders along twelve miles of the Patuxent River – a picture of wild natural beauty set on formerly owned Piscataway Indian lands. At the park’s Visitors Center are Indian projectile points, axe heads, and artifacts from colonial times that have been uncovered throughout the sanctuary. As part of the site the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary with its lush vegetation and noted bird sanctuary is a haven for naturalists, especially during fall wildfowl migration.

Primitive Life Skills instructor, Daniel "Firehawk" Abbott teaches friction fire - photo credit Jordan Wright The event, billed as 3rd Annual American Indian Festival is not what you’d call a traditional pow wow. It has been created as a promotion and celebration commemorating American Indian and Alaskan Native Heritage Month. The Maryland Natural and Historical Resource Division, who hosted the festival with the Clearwater Nature Center and Watkins Nature Center, directs its attention to non-Natives, reaching out through teaching and hands-on instruction in traditional and modern Native American dancing, artisanal crafts, sports and music. Over 2,000 attendees had gathered, eager to learn everything from weaving and archery to tips on how to research their Native American roots.

“We like to have a lot of hands-on participation and no competition, just cooperation and the sharing of knowledge and lore,” says Karen Marshall the event’s coordinator in Prince George’s County for the National Park Service. “The park service makes sure that all activities are staffed and directed by members of the Indian community,” she adds.

Fry bread taco - photo credit Jordan Wright  Steven Hill stirs the Ojibwe Corn Soup - photo credit Jordan Wright A large central stage held two groups of performers who sat facing each other in small circles while the Buffalo Hill Singers chanted in unison to the throbbing drumbeats of the Youghtanund and Turtle Creek Drummers, their incantations giving rhythm to the movements of the hoop and jingle dancers. The audience gathered around tapping and bobbing along to the beat.

During the day several nationally known Native Americans were featured in the program including emcee and hoop dancer Dennis Zotigh, of the Kiowa Santee Dakota and Ohkay Owingeh tribes; author and horse trainer Dr. Ray Charles Lockamy Cherokee; genealogist and family historian Margo Lee Williams, Cherokee; and NMAI advisor and local Native American tourism promoter Rico Newman, Piscataway Conoy tribe, who demonstrated the art of beading and finger weaving. Families wandered around the exhibitions or sat near the stage enjoying traditional foods, storytelling and bareback horse riding demonstrations.

Awaiting entry to the tipi - photo credit Jordan Wright  Dr. Ray Charles Lockamy weaves tales of his youth - photo credit Jordan Wright “It’s very important to have a first person interface with those that are knowledgeable in tribal practices and lore and to learn about Indians where they are rather than watching TV or reading books,” advises Dennis Zotigh who works with the National Museum of the American Indian on Native cultural events.

The Clearwater Natural Dye Group brought a spinning wheel to spin wool from the oldest breed of sheep in North America. And there were samples of the Navaho Churro sheep’s wool tinted with natural plant dyes that had been extracted from Osage oranges, achiote and onion skins to create a myriad of soft-hued colors for the weaving of clothes or blankets.

A former dairy barn became a rustic backdrop for park service naturalists and their “Birds of Prey” exhibit featuring a tiny owl, an American bald eagle and a kestrel along with other local species. Scattered around the grounds were long tables staffed by Scout troops and a host of volunteers teaching families how to make cornhusk dolls, weave baskets and string beads as keepsakes.

Head Dancer - photo credit Jordan Wright Contributing to a day rich in culture Daniel “Firehawk” Abbott, of the Nanticoke Tribe of Eastern Maryland, a teacher of primitive life skills at Historic Jamestowne in Virginia, was in period deerskin clothing. Encamped beside a wooded area he demonstrated the technique of friction fire and other native skills while families, perched on hay bales, listened raptly. Abbott brought his astonishing private collection of Mid-Atlantic Coast artifacts reflecting an extensive array of museum-quality prehistoric tools, weaponry, animal pelts, basketry, ceramics and model prehistoric shelters for visitors to marvel at and to experience hands on.

Cantering through a field on his chestnut horse, Dr. Ray Charles Lockamy pulled up sharply and dismounted before his awaiting audience. He began to weave stories of his upbringing and the horse in Indian life, explaining its use as both protection from danger (by crouching under its belly) and its use in hunting.

While atop a grassy ridge, an archery range was popular with bow and arrow fanciers who lined up to receive instruction, children waited their turn to clamber inside a tipi. Bob Killen of the Pocomoke Indian Nation, builder of the 14-foot tipi, patiently answered questions about Indian life in the Chesapeake region. Storytellers Zak “Between Two Worlds” and Joseph “Stands With Many” invited others to join them around the fireside with Native-spun tales of how bats came into our world and other curious descriptions of the origins of animal life.

Cherokee historian and genealogist, Margo Williams - photo credit Jordan Wright  Redbird Flutes handmade by Roger Bennett - photo credit Jordan Wright Closer to the artisans and vendors musical strains could be heard from Master Flute Maker, Roger Bennett of Redbird Flutes and well-known performer and flutist Ron Warren. Shango Chen ‘Mu and ‘Mahdi played a mystical form of World Music with Tibetan bowls, flutes and a modern steel drum called the Hang.

As the day came to a close and artisans packed up their wares, folks drifted back to their modern day vehicles carrying with them their newly made crafts and a wealth of newly acquired knowledge of Native life. We all left with a stronger sense of community from a peaceful afternoon spent in the woods sharing Native American culture.

For information on Patuxent River Park and the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Upper Marlboro, MD visit http://www.pgparks.com/page332.aspx

|