Jordan Wright

July 15, 2015

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

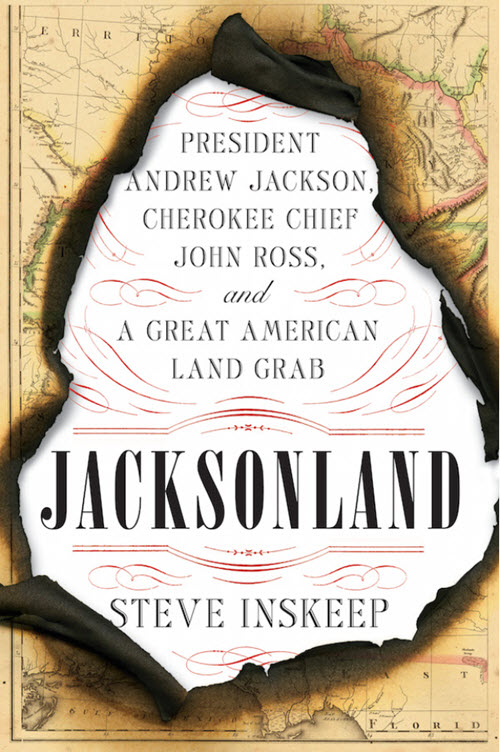

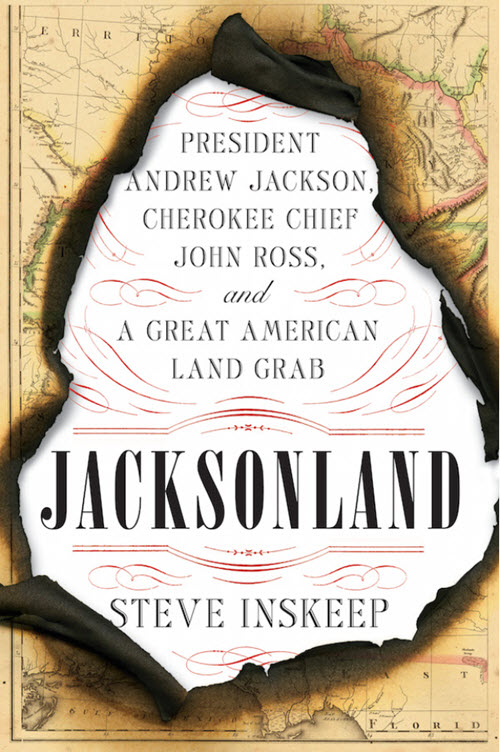

Morning Edition co-host Steve Inskeep’s book Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab tells the almost-lost-to-history story of Cherokee Chief John Ross and his attempts to save the Cherokee Nation from President Andrew Jackson. Photo credit: Penguin Press You don’t need to be a history buff to dive headlong into Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab (Penguin Press, 2015), Steve Inskeep’s riveting masterpiece of two influential men who held radically opposing visions for our country. The well-respected author and co-host of National Public Radio’s Morning Edition recounts in vivid detail the ultimate story of power, ego and greed that was played out in the Deep South (which Inskeep dubs Jacksonland) and which ultimately defined the future settlement of our nascent nation. Coming from relatively humble roots, both men once fought on the same side and later crossed verbal swords in defense of their principles—Jackson, whose desire for personal gain for both himself and his well-heeled cronies translated into immense power and control of the Union, and John Ross, a well-educated and savvy Cherokee Indian chief committed to protecting Indian territories and sovereign rights.

Inskeep toggles between chapters about Jackson and Ross as he methodically lays out their personal journeys, meticulously detailing their early lives, crossed paths, and the events and battles that lead to the ultimate betrayal—the Trail of Tears. But the events do not progress in a straight line. And that’s precisely what makes this a page-turner.

At stake in 1812 were the territories of the Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Seminole, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Creek—whose collective territory extended from the southernmost tip of Florida, around the panhandle to Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, westward along the muddy banks of the Mississippi River to the Missouri Territory, and north in a winding border that extended from the Atlantic Coast south of what is known today as Georgia and along the northern reaches of the Tennessee River. This was the so-called Indian Map. On the contrary, the “White Man’s Map” of the same period laid claim to everything east of the Ohio River and the Mississippi, with the exception of Florida, which was still in Spanish hands.

Known to his people by his Cherokee name, Kooweskoowe, Ross was able to access the “whiteside,” as he called it, using his mixed Scottish and Indian ancestry to straddle both Indian and white political and social spheres. Trained as a lawyer, he sported the sartorial style of white politicians, cutting an imposing figure as he strode through the halls of Congress, negotiating with lawmakers to strike deals favorable to his people. There was no more dedicated and effective representative for the Cherokee, and they trusted and relied on his savvy statesmanship.

But the dark side to this era of Indian relationships with the U. S. government is the backstory of Jackson’s unimaginable greed, ruthless double-dealing and consolidation of power. How he granted favors to and colluded with his associates to obtain land for their personal enrichment, while breaking promises to the Indian nations.

Through personal letters written by Ross and Jackson, and a wealth of documents of the period, Inskeep has achieved an exhilarating read. Outlining the real history of Jackson’s rise to the U.S. presidency, and Ross’s hard-fought efforts for the Cherokee, the author makes it clear that given a few different conditions, the removal of the tribes might never have happened. For example it is stunning to learn that the 1835 Treaty of New Echota, in which the Indians ceded territory and agreed to move west, prevailed by a single vote, even though it had never been signed by Chief Ross or the Cherokee National Council. And that Jackson’s biggest battle may have been his health, which was so poor that frequently he was perilously close to death.

As a seasoned reporter, Inskeep has said he was driven by “the disgraceful politics of the past few years” to write this book. That passion has driven him to give us a clear-eyed and fascinating story of two influential men, one whose democratic values followed the principle of majority rule, and another who represented minority rights. But he has also delivered a cautionary tale of the machinations of the rich and powerful that especially resonates today.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/07/15/jacksonland-riveting-narrative-details-chief-john-rosss-attempts-save-cherokee-nation

JORDAN WRIGHT

July 15, 2015

Special to Indian Country Today Media Network

Author Steve Inskeep, co-host of NPR’s Morning Edition, discusses ‘Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab,’ published by Penguin Press. Photo credit: Linda Fittante Noted author and journalist Steve Inskeep, co-host of Morning Edition on National Public Radio, sat down with Indian Country Today Media Network to dissect his new book, Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab, published this summer by Penguin Press. The book, a riveting masterpiece about two influential men who held radically opposing visions for Turtle Island, brings to light lesser-known facts about this time period that the publisher calls a “crossroads of American history.”

What prompted you to write this story?

I just wanted to tell the whole story, and it was interesting to me to realize how little of the story I knew. John Ross was almost an entirely undiscovered character, an interesting character, and I wanted to find out what made him tick.

What was your reaction when you began to discover a clear picture of interwoven greed and power?

It wasn’t a complete surprise. How it worked, and why, was new to me. It’s understood that there were national security motives and patriotic motives to clear Indians out of the Southeast. But I don’t think it’s as well understood that there were also economic motives and a desire for land and a desire to expand slavery that was behind it and that really drove it. And that Andrew Jackson himself was personally involved in developing the land that he obtained as general. I came across a lot of detail that had never been put together in quite this way.

There were so many moments when things could have gone in an entirely different direction, as when the Indian Removal Act won passage in Congress by only one vote. It seems the press was hugely influential then, creating stories out of whole cloth while spreading fear and innuendo about the Indians. Do you think newspapers were more influential then than they are today?

Newspapers then were more influential because they were the principal form of media. There would have been around three dozen newspapers during late colonial times. By the early 1800s they were in the low hundreds, then very quickly it goes up to around 800 by 1828. Everybody read each other’s papers, and people would send them around by mail.

Do you think Sequoyah’s creating of the Cherokee syllabary in 1821, and its usage in Ross’s newspaper, helped spread the word?

Yes and no. The Cherokee Phoenix newspaper had articles in both Cherokee and English. And so, although it was a cultural triumph to have their own written language in a newspaper, it also had propaganda value. But the real political punch was that editors of other papers would read the Cherokee perspective of events that were different from the White perspective of the same events.

RELATED: Book Strips Away the Myth Surrounding the Cherokee Syllabary

How important do you think Ross’s ability to walk on the “whiteside,” as it was called then, contributed to his success as a diplomatic envoy?

I think it was very important that he was able to speak English and present himself in a way that white men could understand and relate to, and that sometimes he could also pass as a white man. I’m not saying that was good or bad. It was just the political reality of the time. That could also be used to undermine him, though. And it was also used to challenge him. Cherokees didn’t challenge his status as an Indian, but whites would undermine his racial credentials and say he wasn’t Indian enough. So sometimes it was a double-edged sword.

The most important thing was that he was literate in English, could write his own letters and make his own demands, and was not dependent on an interpreter to get across all the nuances of what was intended in agreements. Others who signed treaties may not have known what they were signing. Ross understood the terms and the wider political context of what the Indians were being offered.

What do you think was Ross’s greatest success?

I think it was when he blocked Jackson from grabbing two million acres of land, even though later Jackson went around him. At the end I don’t think it’s widely understood that before the Trail of Tears, Ross improved the terms under which the Trail was to be undertaken. He managed to keep the Cherokees together and get more than $6 million for the land. Though that was not what it was worth, it was substantially more than what the government was offering. At the same time Ross managed to keep the Cherokee government together. All along he was innovative in the use of democratic tools in a way that adds to our democratic tradition and foreshadows a lot of things that civil rights leaders did a century or more later.

In the end, if the tribes had held together and not sold their lands, do you think there would have been a larger war?

We have an answer to that. More or less, yes! We saw it happen in Florida. There was a war that lasted for years. Thousands died, U.S. soldiers, civilians and Seminoles. We’re talking about a really awful conflict for its time, and that, I suppose, would have been the alternative. In Alabama there were Creeks who did not want to go away, and there was an insurgency there in the 1830s. You could have had more devastating wars. There can’t be any doubt about what the result probably would have been, because even if they were all united, they were so outnumbered by then. Had they united in some effective way, you could have had a different course of history. But they didn’t, and when there was an attempt to unite them under Tecumseh, it didn’t turn out very well for the Indian side in the end.

During your extensive research, what surprised you most?

I had no idea that the Cherokees had done so much in their own defense. I think that has been overlooked, even by accounts that were sympathetic to the Indian side. I think Indian removal has often been portrayed as an argument among white people, though there were people who were for it and people who were against it. I’m not sure that the Cherokee participation in the emerging democratic life in the United States has been recognized in the way that it should be.

What would you say are the parallels to today’s struggle for civil rights?

I think some of the same techniques John Ross used were those used by civil rights leaders in the 20th century. Cherokees decided they needed their own newspapers, as did African Americans. They also both realized they needed white allies, and both groups reached out to the religious communities to get some of those allies.

Both groups fought in Congress, and both fought and won before the Supreme Court. In the end though, the Cherokee efforts and victories did not do them a lot of good. While by no means perfect, by the 20th century, racial attitudes were changing and improving, and it was becoming less and less acceptable to argue that there were entire racial groups of people not entitled to become full citizens of the United States.

In the recent campaign to put a female icon’s image on American paper currency, would you prefer to see Jackson removed, rather than Hamilton?

I wrote an article for The New York Times recently in which I proposed that John Ross should be on the twenty-dollar bill and Andrew Jackson should be on the flip side. I think there should be two characters on every bill. Each pairing should be people who relate, so that they tell a story about our democracy and about imperfect people fighting it out about our democracy. Abraham Lincoln could be paired with Frederick Douglas. Ulysses S. Grant on the $50 bill paired with Harriet Beecher Stowe. It would give a greater sense of this grand democratic story that we are all a part of, and the way that different kinds of people participate in that story and have influenced it over time. Jackson and Ross were not perfect people. They were people who fought within the democratic system.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/07/15/author-steve-inskeep-talks-john-ross-andrew-jackson-and-trail-tears-161079

Jordan Wright

May issue 2014

Special to Washingtonian Magazine

Hop aboard Amtrak from DC’s Union Station to the newly hip, historic town of Culpeper, Virginia, where the train lets you off at a visitors’ center in a restored 1904 train station. Across the street, a giant “Love” sculpture made from old film reels hints at your mission: Thursday through Saturday nights, plus Saturday afternoons, the Packard Campus Theater at Mount Pony (19053

Mount Pony Rd.; 202-707-9994)—the Library of Congress’s state-of-the-art auditorium—shows free classic films and foreign documentaries, while Sunday matinees ($6) are in downtown’s newly restored State Theatre (305 S. Main St.; 540-829-0292).

When not watching movies, you can browse East Davis Street’s shops, such as Harriet’s General (172 E. Davis St.; 540-317-5995) for American-made wares, the Culpeper Cheese Company (129 E. Davis St.; 540-827-4757) with 100-plus varieties, and My Secret Stash (162 E. Davis St.; 540-825-4694), where throwback candies share real estate with vintage jewelry and furniture.

Book ahead for a Mediterranean inspired dinner at Foti’s Restaurant (219 E. Davis St.; 540-829-8400). Stay at the Euro-elegant Thyme Inn (thymeinfo.com; from $125), with downy duvets and fireplaces. — JORDAN WRIGHT

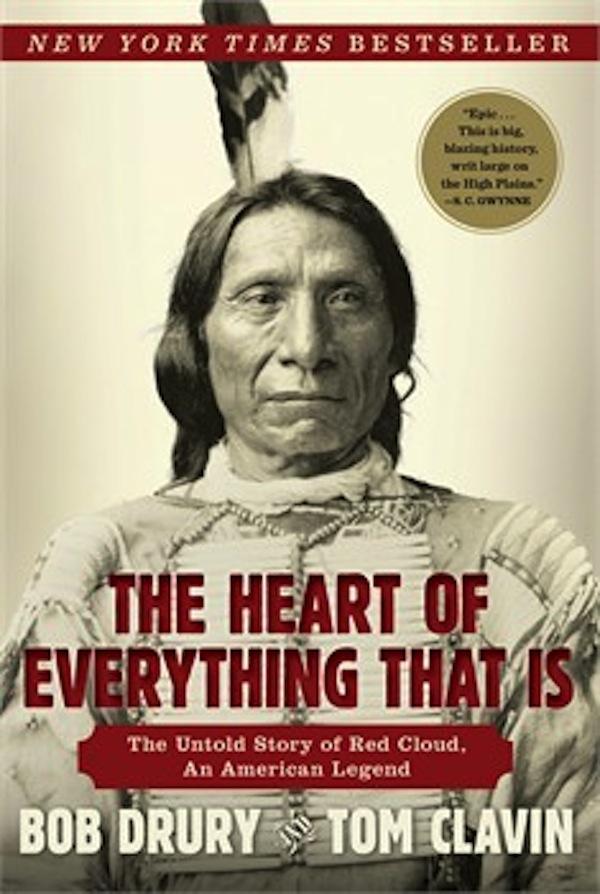

The writing team of Bob Drury and Tom Clavin are best known to their readers as American military historians. Noted for turning out impeccably researched chronicles, their books range in coverage from World War II and Korea to the Vietnam War and usually grace The New York Times bestseller list. But for all their military acumen, the two had overlooked one of the biggest stories in American history: That of Chief Red Cloud, who led the Western Sioux Nation to victory against the U.S.The Heart of Everything That Is: The Untold Story of Red Cloud, an American Legend (Simon & Schuster, November 2013) was born.

Before that, Drury and Clavin had been kicking around a few ideas for their next subject when they found themselves at the Marine Corps Base at Quantico as they accepted an award for Best Nonfiction from the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation.

“After the ceremony a Marine said to us, ‘You do know about the only Indian to win a war against the United States?’ ” Drury told Indian Country Today Media Network. “We said we were familiar with the Battle of Big Horn and other well-known battles. And then he said, ‘I didn’t say battle, I said war! An entire war.’ And I thought, Why didn’t we know about that?”

The Marine then told them about Red Cloud, chief of the Western Sioux Nation. The two were stunned to discover that the warrior in question was not Geronimo, Sitting Bull or Crazy Horse—proud fighters who most schoolchildren are taught about. They knew then that they had their next book.The Heart of Everything That Is tells Red Cloud’s story in his own words (he related his tale to a third party before he died) and lays out a riveting timeline of the period.

In researching his life, the authors uncovered a wealth of material from diaries and letters written by U. S. military officers and their wives and children, and wilderness trackers, plus a treasure trove of historical information gleaned from the letters and journals of the pioneers who crossed the Great Plains during the 1800s. Indian Country Today Media Network caught up with each author recently to gain insight into what compelled them to learn more about Red Cloud and write, “His overall leadership, his organizing genius, and his ability to persuade contentious tribes to band together…had enabled perhaps the most impressive campaign in the annals of Indian warfare.”

Your book is meticulously researched, full of the smallest details of life on the American Plains. What surprised you most in your studies of that period?

Clavin: The biggest surprise was how little we know of Red Cloud in our popular culture. We know a great deal about Geronimo, Cochise, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. But Red Cloud wasn’t discussed at all in our history books. As we did more research we discovered stories of his exploits and of his importance in Sioux society and their culture and history.

It was shocking to us that he was little more than a footnote to what we know about the American West. It’s been mostly the white academics and white scholars who have written about the Indian. The Indian point of view has been mostly through the observation of others, as with Frances Parkman’s The Oregon Trail.

What drew you to the story of Red Cloud?

Clavin: I was reading a description of the Fetterman massacre and Red Cloud and thought I was pretty well versed in eighteenth-century history. But ultimately when we decided to take on the story of Red Cloud, it became a four-year journey.

Drury: We saw his life was rich during the period of Manifest Destiny. It told of a way of life that had gone on for a millennium. We were accustomed to interviewing living people. But what we found was almost like Twitter, everyone kept a journal back then. Tom went to all the historical societies and university libraries out west and found so many letters. Some of the documents were so fragile that we had to handle them with gloves. Reading these journals was like interviewing living people. It was an amazing discovery. For example, no one knew how the Indians ‘treatied’ with each other.

Would the Plains Indians have survived without the trading posts and contact with whites?

Clavin: They probably would have survived much better! The trading posts were very destructive to them. They seduced the Indians from finding their own food and clothing, which they had always done. It also introduced alcohol to them and brought diseases they had no immunity from, like smallpox and cholera.

What was Red Cloud’s legacy to the Sioux?

Clavin: Once he retired as a military leader and after he could see the growing military power of the white people, he wanted to be sure that the Lakota Sioux and their children had education and medical care. He was an advocate in Washington for funds and other resources to come back to the reservation.

What does the book’s title mean?

Clavin: The Lakota Sioux name for the Black Hills ispaha sapa. The area straddles the border between Wyoming and Southwestern South Dakota. They considered it their sacred territory—where they came from. The translation is “the heart of everything that is.”

Does Red Cloud have descendants?

Clavin: Tribal leaders have been descendants of Red Cloud, the leader of the Oglala Sioux, who was considered their leader until he died in 1909. Then it was Jack, his son, then James, his son, then Oliver Red Cloud, his son who died this past July at 93. His son, Lyman, was supposed to take over as leader, but died two weeks later. I have heard there is now a vacuum in terms of their spiritual figurehead.

Do they still live on the Pine Ridge reservation?

Clavin: Quite a few still do. Though some also attend school outside of the reservation and marry outside, there are still grandchildren and great-great- grandchildren living there.

What surprised you the most in your research?

Drury: Well, there were so many things that surprised me. For example, we have the Alamo, the Battle of Big Horn and the Fetterman fight, which somehow had gotten lost in the mists of time. The story is about the demise of one nation, Red Cloud’s nation, and the rise of another nation, the continental power of the United States—and in the middle of it was the Fetterman fight.

Another was old Jim Bridger, the self-taught trapper and explorer. Why were Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, Kitt Carson and all these iconic figures mentioned in our American history books but not Bridger? I think he is the most fascinating character in the book because his story lends so much to the book’s narrative. He and Red Cloud lived almost parallel lives on this vast continent. During this period mapmakers described the vast interior of the country as the great American desert. But during their lifetimes we annexed Texas, fixed the Canadian boundary, defeated Santa Ana and took over many of the western and northwestern states. All of a sudden we were becoming a nation, and at the same time Red Cloud was in charge of what whites considered a nation. So it was inevitable that these two nations were going to clash. And this was witnessed by Jim Bridger and Crazy Horse, among others of the period. I wonder to this day why he is not up there in the pantheon of Western pioneers.

What is your takeaway?

Drury: If we had just honored that final treaty, because Red Cloud’s war never really ended, even though he signed a treaty. It still continues in the courts today, because we broke so many treaties. But if we had just honored that final treaty that ended Red Cloud’s war, this would be a better country today for everyone.

So why did two white guys think they could write about the history of American Indians?

Drury: My only answer is I didn’t serve in World War II, but that didn’t stop me from writing Halsey’s Typhoon and doing a good job of it. I didn’t serve in the Korean War but that didn’t stop me from writing The Last Stand of Fox Company, and I was even too young for Vietnam, but that didn’t stop us from writing Last Men Out. So in the same sense I don’t think color, age or creed matters when you’ve got a ripping good yarn. And this one’s a great saga with epic sweep.

Read more at

http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/03/16/heart-everything-chief-red-clouds-untold-story-revealed-154026?page=0%2C2

Jordan Wright

April 11, 2013

Special to Washington Life

Tally’s Historic District – Park Avenue As Florida celebrates its 500th anniversary of Ponce de Leon’s arrival, visitors to the state should put Tallahassee high on the list of sites to visit. Better known for lobbyists and legislators, Gators and Seminoles, the state capitol is a fascinating historical and recreational locale with as many diversions as a visitor has time to enjoy. “Tally”, as the residents fondly call it, is a surprisingly hip city with restaurants and cafés highlighting both Old and New Southern cuisine.

Along the Native American Heritage Trail archaeology seekers can explore the Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park with its six earthen temple mounds and imagine the ancient Native culture of the Apalachee Indians, or take in 12,000 year-old paleolithic artifacts in the city’s spectacular history museum. History buffs can trace Hernando de Soto’s Trail of 1539 and his winter encampment in Tallahassee and follow the paths of the early Spanish explorers that traded with the coastal city of St. Augustine.

A pelican skims the surface of the St. Marks River – photo credit Jordan Wright Birders can delight in over 372 species of birds that reside in or migrate through this region on one of the country’s major flyways, while eco-tourists can tour thousands of acres of protected wetlands and forests to wonder at the fascinating flora and fauna of the area’s waterways.

First impressions have a way of coloring the traveler’s experience, and Tallahassee gets off on the right foot. To get a sense of how old Florida’s state capitol is, begin in the city’s Park Avenue Historic District with a stroll beneath live oak trees dripping with Spanish moss past Tallahassee’s 19th C architectural gems. If you’re there on a Saturday the “Downtown Marketplace” vibrates with live entertainment, a farmers market, music, arts and crafts, and storytelling for kids. You’ll be on the expansive boulevard known as “Chain of Parks”. From there, go two blocks south to East Park Avenue and tour the William V. Knott House. Built in 1843 and since restored to its 1930’s splendor, this elegant home is where Union troops read the Emancipation Proclamation and where Mrs. Knott wrote quirky poetry that she attached to her furniture.

On South Monroe Street you’ll come up on the Florida Historic Capitol Museum with its magnificent stained-glass dome. A beautifully preserved structure built in 1902 it tells the story of the state’s fascinating political history. Of particular interest is the current “Navigating New Worlds” exhibit featuring the Michael W. and Dr. Linda M. Fisher collection of Old World maps of Florida dating from 1493, one year after Columbus’ arrival on American shores.

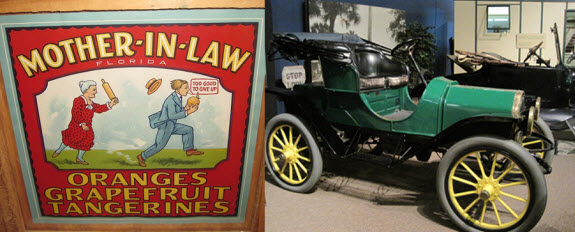

Effigy vessel A.D. 1350-1500 found on Fort Walton Beach on display at the Museum of Florida History – photo credit Jordan Wright On South Bronough Street lies the Museum of Florida History housing exhibits ranging from the prehistoric era to the mid-20th century. With 27,000 square feet of gallery space devoted to over 45,000 artifacts, this remarkable museum is a veritable treasure trove with hands-on exhibits highlighting Spanish exploration and Florida’s indigenous tribes. Be sure to check out the pirates’ booty of diver-discovered jewelry and gold doubloons retrieved form shipwrecks off the coast. Native artifacts and prehistoric skeletal remains are wonderfully displayed and include a full-size mastodon recently discovered in nearby Wakulla Springs. The museum also showcases Floridian curiosities like early antique cars, World War II memorabilia, a collection of early Lily Pulitzer dresses, orange crate labels and unique inventions.

Early orange crate label and 1910 Electric Car at the Museum of Florida History – photo credit Jordan Wright Art lovers can tour the 6,000 square foot permanent exhibit named “Forever Changed: La Florida” highlighting Florida as a colony of both Spain and Great Britain. Current shows include “Reflections: Paintings of Florida from 1865-1965” an impressive 85-piece collection of fine art with Florida subject matter including works by Martin Johnson Heade, N. C. Wyeth and Hudson River School artist, Herman Herzog. The show runs until May 6th.

If you remember the landscape paintings of Old Florida sold by the side of the road between the mid 1950’s to the 1980’s, you’ll appreciate Cici and Hyatt Brown’s collection of the “Florida Highwaymen” paintings that showcases works by 23 of the original 26 artists. Many credit A. E. Backus who taught other young African American students how to paint. For a schedule of lectures, re-enactors and musical performances at the museum go to

Head north and east to South Duval Street and Kleman Plaza, where the Challenger Learning Center boasts a 3-D IMAX theater, a space mission simulator and a 50-foot high Digital Dome Theatre and Planetarium that is out of this world.

The blacksmith at his forge and pumpkin cooking at the Mission San Luis – photo credit Jordan Wright Three miles from downtown Tallahassee is the Mission San Luis, the westernmost of forty-one missions built by the Franciscan monks in the 17th century. The sprawling 65-acre property consists of the only reconstructed mission of its kind in Florida. There are many buildings to explore and costumed docents to guide you through the living quarters and demonstrate cooking, sewing, blacksmithing and archery typical of early life in the mission. The massive church with its huge oil paintings, a 60-foot high Apalachee council house woven of over 100,000 Sabal palm fronds and numerous outbuildings reveal daily life for its inhabitants. At the blockhouse and stockade, cannons dot the palisade as militia masters demonstrate the art of loading and firing a musket.

The reconstructed Apalachee Council House at Mission San Luis – photo credit Jordan Wright In 2009 a large Spanish Colonial style visitor center was completed housing an archaeological research center, art gallery, theater, classrooms, gift shop and banquet hall. Groups can call in advance for a catered lunch of authentic paella, from Valencian chef Juan Ten.

Tree to Tree Adventures Zipline at Tallahassee Museum Minutes from downtown is the Tallahassee Museum – a living museum nestled between Lake Bradford and Lake Hiawatha. From elevated boardwalks it’s easy to spot panthers, bobcats, alligators, black bear and other indigenous Florida wildlife in their natural habitats. Or soar over bald Cyprus swamps on the super cool “Tree to Tree Adventures”. With over 19 zip lines and 70 obstacles, you can view the museum’s 52 acres from the treetops. Back on terra firma join a fossil dig or nature program, or just walk the shaded grounds to see a 1930’s African American church, Jim Gary’s brightly painted metal dinosaur art, Bellevue, the plantation home of George Washington’s great grandniece, a 19th century farm, an 1890’s schoolhouse and the old Shephard’s Mill. You’ll think you stepped into the Florida of days gone by.

Jim Gary’s metal dinosaurs roam the Tallahassee Museum and Gardens – photo credit Jordan Wright Along the Miccosukee Road is the Goodwood Museum and Gardens. A splendid antebellum house reminiscent of Old Florida, it’s filled to the brim with a vast collection of antiques. The property, which once consisted of 2,400 acres, was a former cotton and corn plantation and the home was built in the 1830’s. Its current twenty acres have eleven historic outbuildings and a reconstructed carriage house that is a favorite spot for weddings, conferences and banquets. The beautifully restored gardens feature vibrant camellias, fragrant magnolias, highly scented freesias and row upon row of roses that peak in April. If you are a rose fancier you’ll be wowed at the 150 varieties on the grounds.

The grounds at Goodwood Museum & Gardens in Tallahassee – photo credit Jordan Wright A handful of historic homes and smaller museums are just as intriguing. Tallahassee Antique Car Museum, Mildred and Claude Pepper Library & Museum, Beadel House at Tall Timbers, John G. Riley Museum of African American History & Culture, Maclay Gardens and State Park, and The Kirk Collection.

STAY

The Sheraton Four Points Downtown is conveniently located in the heart of Tally.

The Hotel Duval is an upscale boutique hotel with a modern, hip dynamic. Visit the rooftop restaurant and Level 8 Lounge for a fabulous sunset view of the city and craftmade cocktails.

DINE

There are a myriad of options for dining in this hip, vibrant city where chefs have caught on to the locavore movement in a big way.

Mini crab cakes at Avenue Eat & Drink – photo credit Jordan Wright Avenue Eat & Drink

Upscale wining and dining in a casual setting. Check the blackboard for specials and let the sommelier pair your meal from their extensive wine cellar. Expect organic meats and local produce from Executive Chef Greg Brown.

Lobster Benedict and a plate of the “Slutty Brownies” at the Paisley Cafe – photo credit Jordan Wright Paisley Café

This adorable spot in a clapboard house has the best sandwiches and baked goods in Tally. Try their chef-driven brunches on Saturdays and Sundays with Aunt Ruby’s hoe cakes, real Southern biscuits, lobster benedict and housemade berry tea. Take home a bottle of Tupelo honey and a “Slutty Brownie” from the bakery case.

The Paisley Cafe in Tallahassee – photo credit Jordan Wright Cypress

Sophisticated Southern dining with exquisite gourmet dishes and cocktails alongside works from local artists. Order a platter of artisan-made cheeses including Sweet Grass Dairy’s “Green Hill” made in nearby Thomasville, GA. Try a “Gallagher” cocktail made with cane rum, pineapple, ginger and a combination of cherry and apple liqueurs.

Shula’s 347 Grill

Aged Black Angus steaks and double-cut chops get top billing at the Hotel Duval.

Sweet Pea Café

Delicious vegan and vegetarian lunch and dinner till 8pm in a cute tin-roofed barn-red restaurant.

Chef Matt Hagel and Owner Ruben Fields Miccosukee Root Cellar Focuses on Local Flavors –

Photo by Scott Holstein Miccosukee Root Cellar

Farm-to-table dishes from Executive Chef Matt Hagel who sources organic products from over a dozen local farms. Housemade breads, ice creams and desserts plus a collection of craft beers including Big Nose IPA from Swamp Head Brewery of Gainesville, FL. Live music on the weekends.

ST. MARKS AND WAKULLA COUNTY

A side trip to Wakulla County, a 30-minute drive from central Tallahassee to the Gulf, should be on everyone’s itinerary. For nature lovers this area of beaches, marshes and pristine estuaries at the east end of the “Forgotten Coast” is unparalleled. Guided tours of the waterways by kayak or canoe are easily arranged, as are scuba and snorkeling adventures in the blue green waters to explore Wakulla Springs, the deepest and longest known submerged freshwater cave system in the world. Birders take note: It’s a flyover site for the endangered whooping crane.

Of particular interest to historians is the San Marcos de Apalachee Historic State Park situated at the end of the Tallahassee/St. Marks Historic Railroad Trail, an abandoned former rail line to the coast where walkers, equestrians and cyclists enjoy the 19-mile flat-as-a-board pathway. The park sits strategically along the St. Marks and Wakulla Rivers and contains the ruins of a Spanish fort first built of wood in 1679 and fifty years later reconstructed of stone. Civil War buffs will know the presidio as a military post and cemetery for Andrew Jackson’s troops in 1818.

Beer boating along the St. Marks River at the Port – photo credit Jordan Wright At the end of the road is the quaint town of St. Marks, a small port noted for its historic lighthouse and crab processing plants. It is here that you can catch a ride on a peaceful solar-powered boat along the St. Marks River escorted by a Green Guide Master Naturalist. Herons of all varieties as well as manatees, bear, ibises, turtles, alligators and leaping mullet are easy to spot through the long-leaf pines and tupelo trees.

STAY

Wakulla Springs Lodge build by Edward Ball 1937 Wakulla Springs Lodge and the Wakulla Springs State Park – Docent and historian, Madeleine Hirsiger Carr has written a fascinating book chronicling the restoration of the magnificent lodge built by Edward Ball in 1937.

The Sweet Magnolia Inn – A charming bed and breakfast constructed of solid rock and coquina shells, that once knew life as a general store, a brothel and even the City Hall. Each room has its own Jacuzzi tub. Bikes are available to rent. On Sundays the inn serves casual food and a jazz band plays till early evening. Call in advance and genial owners Denise and Andy Waters will cater a delicious lunch with wine and beer or a cocktail spread of cheeses and hors d’oeuvres and deliver it to your boat for a sunset cruise. Her shrimp salad is legendary.

Shell Island Fish Camp, the oldest fishing camp in Florida. Anglers can catch speckled trout, red fish, blue fish, tarpon, cobia and more.

DINE

Boat or drive to the Riverside Café for local grouper, Gulf shrimp and mullet. Blue crabs all year and stone crabs from October through mid-May. Wash it down with a frosty 420 IPA from Georgia’s SweetWater Brewing Company.

Appalachicola oysters ready for the grill – photo credit Jordan Wright Deal’s Famous Oyster House has its share of seafood too – grouper, flounder, catfish, scallops and plump Apalachicola oysters. After all that’s what we came for. There’s no alcohol served in this family style spot, but the restaurant has a specialty you won’t find anywhere else. Something the old folks call a “pogo stick” which is an old time percussion instrument on a tall stick with a cymbal on top and a drum connected to it. When waitress Zodie Horton bought the place from the Deal family she learned to play it from Mrs. Deal. Expect to hear songs like “Cotton Eyed Joe” and don’t be surprised to see locals joining in on spoons or washboard. On Port Leon Drive next to the post office or access by boat from the St. Marks River.

In nearby Crawfordville try the family-owned Spring Creek Restaurant, another old-line Florida spot where you’ll find oyster stew, crab cakes, fried quail, hushpuppies and tomato pie. Wakulla Adventures now offers a sunset cruise from there.

FESTIVALS

“Wild About Wakulla Week” is a week-long festival bracketed by two popular festivals, The Sopchoppy Worm Gruntin’ Festival held the second Saturday in April and the Wakulla Wildlife Festival. A two-day event held the third weekend in April.

WILDLIFE TOURS

Arrange Wakulla Adventures solar boat tours through Palmetto Expeditions who can also help with certified birding and wildlife guides, fishing and scenic cruises, historical walking tours, scuba and snorkeling gear rentals, and specialized catering.

Jars of local mayhaw jelly at Tomato Land – photo credit Jordan Wright On your way back to Tally be sure to stop at Tomato Land for wild mayhaw jelly, pecans, local hot sauces and stone ground grits. The kitchen makes oyster and shrimp po’ boys and fried green tomato sandwiches. Fish Fry Fridays platters come with cheese grits, coleslaw and hushpuppies. A small farmers market with locally grown produce is next to the parking lot.

Kevin Welch is helping Eastern Band of Cherokee growers save heirloom vegetables from extinction. (Courtesy Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Cooperative Extension)

Ask Kevin Welch what he does, and he’ll tell you he’s a “professional farmer.” But he’s no ordinary farmer.

In his unique role with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ Cooperative Extension, Welch has become a nationally renowned speaker on health, nutrition and the benefits of traditional agriculture. He has served as a lecturer-in-residence at Purdue University and spoken at the University of Georgia as well as to the Association of American Indian Physicians in San Diego, California and Anchorage, Alaska, preaching the importance of traditional plants and their roles in combating diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and depression.

But in his day-to-day life, his passion is preserving the heirloom seeds of his heritage. And that’s what makes him a farmer.

In 2007, Welch established the Center for Cherokee Plants, headquartered in the Great Smoky Mountains of Western North Carolina on the Qualla Boundary. The project is funded by the Federally Recognized Tribes Extension Program, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Cherokee Choices Healthy Roots Project through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Welch’s interest in preserving traditional Cherokee methods of farming, creating a heritage seed bank, and sharing with the community is known far and wide. And he regularly receives donated seeds from growers who have passed them down from generation to generation. Though some of these seeds were cultivated for centuries by Cherokees, the tradition of growing these ancient crops had been all but lost. Welch’s mission is to preserve and propagate plants that are considered culturally relevant to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and to maintain a seed exchange program for enrolled members who agree to grow the seeds in isolation, thus keeping them pure, and to share 10 percent of their first harvest with the Center.

During growing season, Welch’s office is an ordinary single-level white outbuilding off U.S. 19 beside a large open field where he tends to his crops on a two-acre parcel of land alongside the Tuckaseegee River in a fertile valley. On the same stretch of ground lies the sacred Kituhwa Mound—the site of the first Cherokee Village.

The long concrete structure, once a former dairy, is used mainly for farm equipment, but it is here in a small room where Welch first carefully records the history and provenance of the rare cultivars.

Harold Long, an Eastern Band member, and his wife Nancy are locals who have benefited from Welch’s seed exchange. Their three-generations farm is a mile higher in elevation from the valley below, and they seek out plants with a shorter growing season—plants like Harold’s mother and father grew.

“We grow seventeen types of heirloom tomatoes like Cherokee purple, Aunt Ruby’s German Green, Mortgage Lister and Violet Jasper, which is small and very beautiful,” says Nancy. “Our pole beans are all string-less—October bean, Lazy Housewife, greasy bean and Cherokee butter bean. We collect our seeds or get them from the extension. We also have the older varieties of apples on our farm, like Moonglow and Liberty. We keep patches of sochan [a relative of the green-headed coneflower] and ramps too.”

Along with hundreds of other gardeners, the Longs have become part of the ever-expanding circle of heirloom plant growers, and their farm a testing ground for these ancient seeds.

In a recent interview, Welch spoke to Indian Country Today Media Network about the program’s promising future.

What are you doing now?

We have a project calledDa gwa le l(i) A wi sv nvusing an enclosed trailer we call the garden wagon. We converted it into a space for holding educational courses. We can set it up at any venue and be ready to teach in about 15 minutes. In remote places where it’s hard to get people to a community center, we can bring it right to them.

We also have a garden kit giveaway program coordinated by Sarah McClellan, project director and educator of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ Cooperative Extension, and funded for the past 10 years by Chief Michell Hicks’ discretionary fund. In addition to organizing the volunteers and selecting locations, McClellan determines all the plants and seeds we give away.

Volunteer Kevin Welch unloads Garden Wagon plants. (National Institute of Food and Agriculture) How are the seeds kept?

We collect them and dry them and put them in the freezer to kill off any pests. Then we sort and clean them and store them in bulk. It’s actually very low-tech. We hold seed saving workshops to teach the basics. Sharing them and planting them is the best way to keep a viable seed bank.

How are they shared?

We provide the seeds to enrolled members only. We don’t sell seeds. Sometimes I bring seeds along with me when I give talks, but then I’m mostly talking about the practical applications, local foods and agricultural education.

All tribes have some aspect of agriculture—from aquaculture to agriculture to ranching. A lot of tribes, when they try to modernize, tend to get away from their traditional agricultural heritage.

Who are some of the people outside the immediate community you have you given seeds to?

We gave seeds to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. for their garden and also on the Earth Day event to the [U.S. Department of Agriculture’s] “People’s Garden” when I came and spoke about gardening. Several years ago, we donated seeds for a rare Cherokee flour corn; Cherokee Speckled butter beans; “Candy Roaster”, a variety of winter squash; and a mix of October beans, to Michelle Obama’s White House garden.

And to start their seed program in the Western Cherokee Nation, we have given 24 varieties to Pat Gwin [director] and Mark Dunham [natural resources specialist] with the Cherokee Nation Natural Resources.

How many different varieties do you have now?

We have many varieties but we only grow out a few each year. We rotate them to build up a stock. My job is to plant, care for them and harvest them. We have quite a few folks that support our program and bring in heirloom seed that has been grown in their family for a long time. We grow varieties of tomatoes, the Cherokee Tan pumpkin, corn, beans, peppers, Jerusalem artichokes and gourds, as well as non-traditional varieties like vetch and wild potatoes from the Americas.

How do you process the seeds you receive?

When we get them, they are catalogued with a story about their heritage. Then they are dated and labeled. Afterwards, we grow them out to see if they are a stable variety, and we’ll take as many seeds as we can. We give away the seeds for free, because the idea is to get as many people growing it as possible, so the variety doesn’t die out.

What about the stories the families tell about their seeds?

That’s an integral part of its being an heirloom and being around so long. If no one liked it, then they would have not grown it anymore. I tell people that without the story of why it’s important to anyone—a seed is just a seed. This is called “memory banking”—the process of gaining the story behind the plant or behind any social construct. The same application is done for the seeds and the plants, like who grew them, why they grew them and why they liked them.

Are they more disease resistant?

Most open-pollinated varieties evolved because they have traits for a certain area. It really goes to soil conditions, environment, pH levels, climate—even the topography of where they come from. Basically they are grown because theyarepest and disease resistant. Sometimes people do what they call “high grading,” selecting the ones they like until they become the dominant trait.

Have you found traditional and natural ways to combat pests and disease?

Most of it is really basic. You can plant companion plants like beans that are a good nitrogen fixer for corn [and] squash, because its broad leaves shade out other plants for a natural weeding effect, and certain types of flowers that attract desirable insects. In winter, we collect praying mantis chrysalises that we place in the garden in springtime, where they’ll hatch out and eat the aphids. Also important is to select the right slope and drainage to prevent mildew from overly damp soils.

What are the challenges to growing these seeds?

The only challenge is crossbreeding and the application of pesticides and fertilizers, which we do not use here; also the elk that roam free here, or even the neighbors’ critters!

Do you have fruit seeds too?

Yes, we have Junaluska apples and Nickajacks—both documented as over 100 years old; Buff apples that are a variety documented to have been grown for at least 150 years; and the heritage White Indian peach, very small and sweet, that the elders really enjoy; also ground cherries and persimmons.

Do you teach people how to prepare the fruits and vegetables?

Most families still know how to cook these foods. It’s generally passed down from mother to daughter, though there are several cookbooks out by enrolled members. The Big Cove Community Club recently held a workshop about traditional cooking. And if you ask at the elementary school, the kids all know whatsochanand ramps are and how they like to eat bear and deer meat.

What are your plans for the future?

Hopefully we will continue to enhance and develop our programming to reach a broader audience. We want to focus on growing more varieties and developing a program customized to different groups. One of the things we’re trying to do is to re-educate the youth so that they’ll have a set of life skills. In this way they will be able to grow their own foods and pass that knowledge along. Our emphasis will be on education and youth gardening because the children are the ones that will carry on the traditions to future generations.

|